Audit Scotland has recently published their assessment of the progress with health and care integration in Scotland. Helpfully, as I was preparing a presentation for an English conference on how we tackle this issue in Scotland. You could be forgiven for missing this report as it came out on the day of the Brexit resignations.

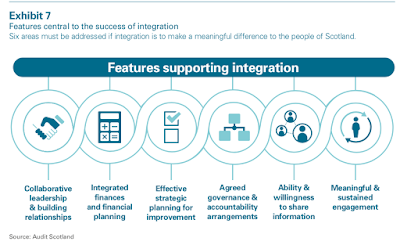

As usual, they introduce the report with a helpful infographic which captures the key challenges. Integration Authorities (IAs) manage a huge proportion of the Scottish budget (£9bn) and are supposed to achieve £222.5m of savings - an increase of 8.4%.

The positives are that IAs have started to introduce more collaborative ways of working and there are a number of case studies in the report that highlight best practice. This shows that the system can work, however, yes you knew there would be a but, “there is much more to be done”.

The building language then starts to break down.

The main problem is that financial planning “is not integrated, long term or focused on providing the best outcomes for people who need support”. This is caused by the financial pressures on health boards and councils, compounded by health boards not including their acute services to the process of budget shift. Long term planning is difficult when budgets are set annually, with little medium term, let alone long term, strategic planning. However, an overall underspend by IAs of nearly £40m does not inspire confidence either.

This doesn’t mean that there is no resource shift because the ISD cost data published yesterday shows a loss of 429 hospital beds. This data also shows that community services are getting more resources, with only a 0.1% increase in hospital spending as against 4.8% in the community sector. GPs have pointed to the fall in the amount devoted to GP services, but this may be related to service redesign. Either way, while there has been some shift from acute to community, progress is slow because of the overall financial position.

The report also highlights a lack of collaborative leadership and strategic capacity, not helped by a high turnover in IA leadership teams and squabbles over governance arrangements. Cultural differences between partner organisations is another barrier to achieving collaborative working along with the necessary skills to work in partnership. This was predicted and has been a problem all over the world (see Petch et al) with care integration.

Workforce planning is crucial to the success of care integration. While the National Workforce Plans have now been published, they are still largely at the process stage, particularly in social care. There needs to be a better understanding of future demand, how this is likely to be met and what it will cost. Needless to say, Brexit looms large over this issue. Attempts by some IA leadership teams to promote the privatisation of services has not helped to build confidence. As UNISON surveys have shown, the procurement rules are not being followed properly. If they were, the two-tier workforce provisions (s52) would end this nonsense.

Data sharing and incompatible IT systems are another problem. There are too many local fixes rather than considering a single national solution. Interestingly, the report points to bringing staff together under one roof, rather than solely relying on IT. This is something that the Quality Care Commission recommended in 2015.

Many of the challenges facing care integration in Scotland can be fixed as local best practice shows. There are some national actions that can help, but there is nothing in this report that wasn’t predicted or points to unresolvable structural failure. The underlying problem is austerity - making big service change is doubly difficult when the budget simply isn’t keeping up with increased demand.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed