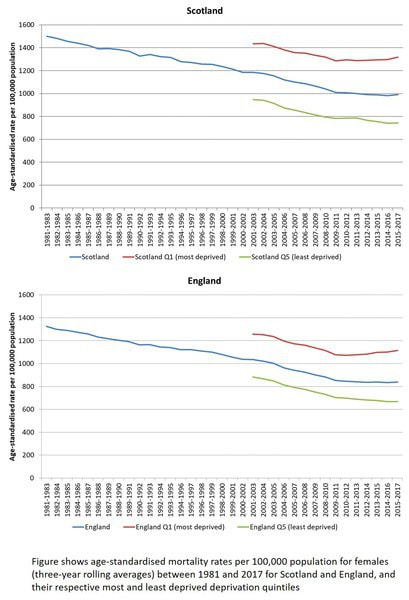

Mortality rates in Scotland and the UK have fallen consistently over centuries. However, since 2012, the rate of improvement has slowed, with a ‘levelling off’ of previously falling rates – and some suggestion of increasing rates in some parts of the country. This is unprecedented and is indicative of serious problems occurring in society.

There were four key findings:

- The stalling or slow down of improvements in mortality happened across the countries and cities in the UK.

- The data masks increasing death rates in deprived communities, widening mortality inequalities.

- There are a broad set of different causes of death. These include both chronic conditions such as respiratory and cardiovascular diseases, as well as more socially influenced causes such as alcohol and drug-related deaths.

- Scotland stands out in terms of its much higher rates of drug-related deaths. Among all the UK cities, Dundee now has the highest rate of death for this cause.

“the most likely explanation for these trends is the UK Government’s programme of so-called ‘austerity’: unprecedented cuts to public spending including social security budgets, which has impacted on the most vulnerable members of society. It is therefore important to use this evidence, alongside other research findings, to bring about changes in policy to protect the health of the poorest and most vulnerable in society. In addition to the action that must be taken at a UK level to address this, the research emphasises the importance of using all devolved and local powers and opportunities that exist to mitigate the effects of such policies and protect and improve the lives of all in society, particularly the most vulnerable.”

Commenting on the paper Danny Dorling points out that; “Outside of wartime, pandemics and epidemics, increases in mortality rates are unprecedented in the UK in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. This rise in deaths has coincided with the imposition of austerity which has most harmed people in poorer cities….the deterioration of the health of the population in the decade before the pandemic struck meant that when it struck, we, and especially those in the poorest places, were weaker than before.”

A further paper written by Gerry McCartney (Sociology of Health and Illness) and others examines power inequalities, including discrimination, to explain inequalities in health outcomes. This distinguishes from behavioural or other explanations of the inequality between the working class and the rest of the population. They map different forms of power and the space they operate in to inform action.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed