It’s not because it is a rare condition. Between one in three/four people in Scotland are affected by a mental health problem each year. The most common illnesses are depression and anxiety. About 1 in 8 of Scots (12%) take an antidepressant every day.

Mental health is also the leading cause of sickness absence in the UK, with 70 million days of work lost each year due to workers suffering from stress, depression, and other mental health conditions. This costs the economy around £26bn a year – or £1000 per employee.

Like most other health conditions it is those in lower income groups that suffer the most. People living in the most deprived areas are more than three times as likely to spend time in hospital as a result of mental illness compared to people living in the least deprived areas. The suicide rate is more than three times higher in the most deprived areas compared to the least deprived areas.

Data on mental health services is patchy and not updated as often as other services. A quick glance through the ISD data shows problems with classification. There is decent data on hospital admissions as you might expect, but this is less relevant given the shift from hospital to community services.

What we do know is that people are waiting a long time for specialist care. Less than ambitious targets came into force last year to reduce long waits to see a specialist, however most health boards have not been able to meet them. 81% of people saw a psychologist within 18 weeks, against a target of 90%. 73% of children saw a specialist within 18 weeks, against a target of 90%. Children are waiting slightly longer than they did in 2014 and 2015. The outpatient waiting time target for physical conditions is 12 weeks.

Even this doesn’t tell the whole story. 85% of GPs told SAMH that there were gaps in service provision for patients and 87% of responding GPs said they wanted more information on local social prescribing services. Delays in treatment are a particular concern because the longer a someone has to wait, the more likely it is that their mental health will deteriorate.

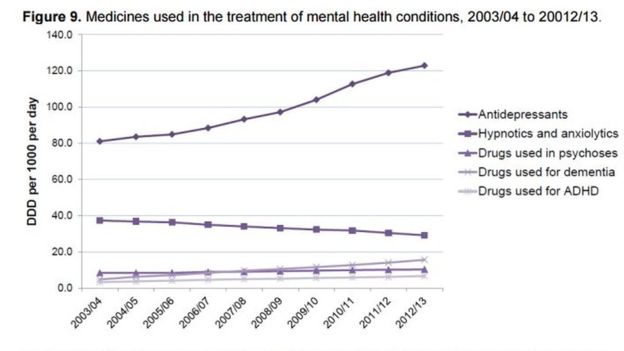

As the stigma traditionally associated with mental health reduces, the demand for services is increasing. There has been a 15% increase in drug treatments in just three years.

Anita Charlesworth, from the Health Foundation, said: "Mental health hasn't increased as a share of NHS funding, despite the fact that there are huge demands on the system, and access to care for mental health still falls way below that for physical health.”

In Scotland, mental health spending was up just 0.1% last year, and down a projected 0.4% this year. Although again spending data is patchy and probably doesn’t capture the range of service providers fully.

Last year, UNISON Scotland surveyed its members who deliver mental health services. They reported that resources are getting tighter. 76% of staff surveyed reported cutbacks in their workplace in the last three years. Staff working for charities/third sector report sharp funding cuts and consequent redundancies. Staff in local government and the NHS point to cuts being carried out via non-replacement of staff that leave, or replacement by lower grade staff. Cutbacks on training and opportunities for Continuous Professional Development (CPD) are also widely reported.

The pressure on staff is not limited to mental health professionals. UK police are spending as much as 40% of their time dealing with incidents related to mental health problems. There are similar issues in our prisons.

So, what should we do about mental health services? Organisations like SAMH have published manifestos for the coming elections and they point the way to a new approach. Scotland doesn’t even have a mental health strategy as the current plan ran out in 2015.

Some key actions could include:

- Parity of esteem with treatments for other illnesses including a properly resourced 12 week waiting target.

- Better information on mental health services in each locality including the range and rate of social prescribing.

- A new workforce plan that delivers staffing numbers to address increasing demand. Suicide intervention training should be a core element of CPD for a wider range of staff.

- Continued funding for the See Me campaign to tackle stigma against people with mental health problems, including a renewed focus on the workplace and in schools.

While the data and strategies could be better, we at least know that Scotland’s mental health services are under severe pressure. We should do much more.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed